Trout Fishing in Kenya

by Briam M. WiprudAfrica and trout are not synonymous. No doubt, this is in large part due to the continent's reputation for game-filled savannas and dense, steamy jungles.

Tarzan wrestled crocs and lions, not brookies and rainbows.

Maggie's and my primary objective in going to Kenya was to do wildlife photography, but as a seasoned traveler to far-flung places,I know that trout can be found in what would seem the most unlikely places. And so my inquiries began, and proceeded very slowly indeed.

A website fishingafrica.com has a subsection on Kenya that gives scant mention of trout. Numerous messages I placed on their bulletin board jammed with talk of yellowfish, tiger fish and kurper - went unanswered.

A book entitled African Fly-Fishing Handbook by Bill Hansford-Steele devotes a couple paragraphs to fishing the Aberdare Highlands, a 60 kilometer-long park north of Nairobi. While this book is an enviable compendium and quite thorough on many aspects of fishing Africa (complete with color plates of regional flies), when it came to the Aberdares it was short on specifics, maps and references that could put you on the stream. Both sources indicate trout fishing in South Africa is more established.

Tamu Safaris, our travel agent, looked into the matter and arranged a tented camp called Sangare from which we would be guided into the Aberdares. I still had no solid idea what flies to bring or whether I needed to lug waders half way around the world for one day's fishing. Also on my mind was whether there were really any trout. Reputations linger. On occasion, I've gone to a remote location only to find that fish once in great numbers disappeared many years past.

The clouds finally parted when I got a response to a message posted on virtualflyshop.com from an American in Nairobi who fishes the Aberdares regularly. He explained that the terrain was moorland at an altitude above 10K in the vicinity of Mount Kenya, and that the small clear streams remained full of brown trout stocked long ago by the British. As the book had suggested, the flies used are sundry local attractor patterns such as Mrs. Simpson (a wide-profile streamer) or Kenya Bug (a simple gold-ribbed black nymph), and the fish see precious few anglers. Hip boots would do fine. My itinerary would coincide with the beginning of the rainy season, so there was the risk that both the route and the streams might be muddy. In other words, the challenge would not be the naïve trout but the long trek just to get them. This is somewhat typical of exotic fishing travel.

Rutundu Lake was also enthusiastically recommended. It's an alpine lake northeast of the main peaks of Mt. Kenya that boasts large rainbow trout. This is across a plateau from Aberdare National Park, and we could have done a day trip by plane to Rutundu, but the added expense was out of our budget.Mentioned as an afterthought was that fishing the Aberdares requires the angler to watch his back. Lions are par for the course. This quaint detail might have been cause for alarm, but the mental picture of "EATEN BY LION WHILE TROUT FISHING" on my tombstone was more dare than deterrent. I had to go.

We arrived in Nairobi on the second of April, and after a night's rest, were shuttled three hours north to the Aberdares Country Club, a lodge that has a trout stream close at hand. (By all accounts, this stream is fished out, and a stream we saw nearby was muddy, slow and unlikely-looking trout water.) Kenyans are understandably proud of suffering dilapidated roads, one of which led right up to a well-manicured golf course, the greens strewn with preening baboons and grazing wart hogs.

At a log clubhouse festooned with flowering shrubs and attended by uniformed staff, we debarked and met our Sangare guide Paul Kabochi, a sinewy fellow with a twinkle in his eye that betrayed considerable experience in the bush. During our treks with him, this inkling proved correct time and again by his uncanny game-spotting prowess, as well as from his anecdotal resume assisting wildlife filmmakers. Paul drove us to Sangare, which was out through the back gate of the club grounds and onto a dirt track far more vehicle-worthy that the cratered highway.

The marvel of Africa's abundant wildlife was quickly apparent even in our short drive from Nairobi to Aberdares where we'd seen ostrich and zebra. On the forty-minute mid-day drive to Sangare, we saw waterbuck, go-away birds, suni (a rabbit-sized antelope) and in a marsh just short of camp, the first of many elephants. By comparison, drive through forested areas in the US or Canada for hours and see nary a chipmunk. Sangare is one of four tented camps owned by Savannah Camps and Lodges. It is situated just to the northeast of Aberdare National Park and next to a large plateau overlooking the slopes of Mt. Kenya to the east.

The camp itself is on the edge of a large pond chock-a-block with ibises, Egyptian geese and myriad other birds. Accommodations consist of a limited number of well-spaced wall tents on raised platforms. Appointments were comfy, consisting of mattresses on simple frame beds, soft linens, thick blankets, battery-operated lamps and full bath complete with hot water. This was not camping in any sense of the word, for which Maggie was grateful. There is no electricity, and the dining hall is lit entirely by lamps and a fire pit. Sangare is rustic yet expansive, clean and well appointed.

After a late afternoon horseback ride amongst zebra and Thompson gazelles on the adjacent plateau, we settled in for a Tusker beer fireside at the pond's edge as the sun set and the chill night air descended. Dinner would have to wait until later. Night game drives are permitted, and so we set out on foot to circumnavigate the pond looking for big-eyed arboreal critters like bush babies and hyraxes. While we didn't see any bush babies that night, we did interrupt a leopard stalking waterbuck, a memorable eruption of confusion, glowing eyes, pounding hooves and whirling flashlight beams.

Dinner by lamplight was with the camp manager, Sammy Kabaiko. Both the meal and company were hearty. Sleeping was fitful, as it often is before fishing a new and exciting location, but particularly so due to the screech and croak of the tree hyrax (a guinea pig-like ungulate with a healthy set of lungs) accompanied by the squawk of arguing ibises and geese. We had to be up before dawn, and the local fauna made sure of that.

The drive into Aberdare National Park took us back through the country club and a half-hour beyond. There's a formal gate where permits are purchased for entrance, after which the road is a steady climb through jungle draped in Spanish moss. Elephant dung led the way up through a precipitous gorge and flocks of silver-cheeked hornbills and the stray vervet monkey and buffalo. The forest eventually thinned until tall bushes lined the road. Leveling out in the 10K vicinity, a vista of open grassy moors and rolling hills splayed out ahead, terrain instantly reminiscent of certain sections of Yellowstone.

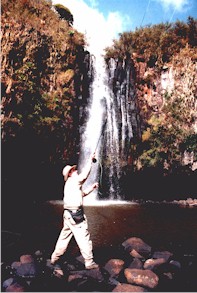

Trout time was close at hand, and our first stop was the Chania River, a cold, clear freestone creek that would put a tingle in any angler. A sign painted on a rock at the small parking area warned: "BEWARE OF LIONS." We took a short walk to look at a waterfall just down stream, and our guide Paul said that a popular way to fish the streams is to go from stream to stream fishing only the base of the waterfalls. I was ready to rig up right away, but Paul said we needed fishing licenses first, and so we made the trek further along to a ranger post before descending on the Upper Magura River.

Above the falls, the stream was no more than twenty feet across: not large. Here there were some small shelters -as at several other locations in the park - that can be rented for those wanting to put in a few intensive days of fishing and camping. At that altitude, the hike down the steep trail the base of the waterfall left us winded, and when we reached the bottom, it looked like I wouldn't need the hip boots after all. Nature had randomly placed rocks from which the entire pool - about 40 by 60 feet - could be reached. The water was in the low sixties and slightly brown with silt. Above, a plume of water fell a 80 feet into the pool.

I rigged up my five-weight, tied on a #6 black wooly bugger and had a follow on my first couple casts. I switched to an olive bead-head wooly bugger and immediately hooked up with a twelve inch brown. I horsed the first one in to make sure I could say I got at least one, and the mahogany fish in my hand had the largest red spots I'd ever seen on a square tail - a truly gorgeous, wild fish. As Paul and Maggie watched and photographed, I took another three fish from the pool, none larger than thirteen inches. As it happened, I had been unable to procure native flies, and was relieved that standard American patterns would take fish.

Paul was philosophical about the lion situation, demurring when it came to talk of carrying a gun. He said there weren't as many lions these days, that they weren't very aggressive and that you could throw rocks to chase one off. As long as you kept an eye out the risks were very slim. Paul also said he was once camping in that area and a lion lay on the side of his tent, taking advantage of his body warmth without taking advantage of his body's nutritional value. His anecdote didn't make me feel any more secure, but if he wasn't worried I didn't see why I should be. Since he was standing on the stream bank, they'd

get him first.

I asked whether one could fish downstream from the falls, and Paul said he'd done so but that the bushes are very close and the wading difficult. Besides, other waterfalls awaited us.

The next stop, I believe, was Gura Falls. (Paul wrote down the names of the streams, but they didn't always match letter for letter with those on the map I acquired later.) This river was remarkably similar to the previous two locations. The angling played out identically to the prior stream, and I quickly took four fish, including one trout on a stimulator right up close to where the water plunged into the pool. Paul had asked if he could keep some of the fish, and when I landed one I would toss it to him where he lay on the grassy bank.

We hit the third spot around noon, and the equatorial sun was bearing down. Paul called this river Chania Karuru, apparently further upstream from where we'd first stopped but had not fished. The waterfall here was only eight feet high and the topography more open to traditional stream tactics. But the banks were high and the fish - which were in abundance - very spooky. Paul and I found a dying trout with a bite taken out of it, and we'd probably just chased off some critter doing a little fishing of his own, which accounted for the skittish trout. Some slack water above the falls had some lily pads, and I elicited a few rises that didn't take before I put them down.

The day was now hot and bright to the point most anglers know their time would be better spent taking a siesta than chasing reluctant fish. And from my high-altitude climbs at the waterfalls, I suddenly found myself exhausted. We did a game drive all the way back to the park entrance, replete with eagles, owls, colobus monkeys, and elephants crashing through the jungle. The whole day we saw only one other vehicle in the park and no other anglers.

While I have many miles yet to travel in pursuit of fly fishing, I feel it's safe to say there will be few more exotic locales for trout than the Aberdares. Any angler who finds himself destined for safari in Kenya would be remiss not to take advantage of this unique opportunity not just to get some exotic trout, but also to experience a truly spectacular aspect of the African landscape and fauna not found in many of the more frequented destinations.