SOUTH AFRICA'S KAROO: By Campervan

by Laurianne ClaaseThe last time I attempted the trip into the thirsty interior of South Africa's Karoo, my ageing pickup refused to co-operate. This time, I came prepared. We were power-steering seven metres of turbo-driven, air-conditioned mobile home; toting a 140 litre water tank, hot and cold water shower, a gas stove and microwave and a fridge well-stocked with cold beer, should summer still linger in the April desert that lay before us.

The Karoo earns its name from the Hottentot for "thirstland". And so it may seem at first. Two hours north of Cape Town, the Great North Road presents the uninitiated with a vast and inhospitable dryness, the sage and khaki monotony relieved infrequently by a solitary farmhouse or windmill. Until, that is, you reach Matjiesfontein. To leave the highway and venture into this African outback is to travel back in time.

Victorian establishments, rescued from the past, line the dusty railway siding. Willowy fronds drip pink peppercorns at the foot of wrought-iron lampposts and the long-empty fountains in the courtyard of the Lord Milner Hotel recall the village's glory days as a Victorian health spa. James Douglas Logan, a Scottish adventurer, opened his Waterworld resort in November 1889, scant years after the invention of the windmill opened up one of the driest parts of the country. While Matjiesfontein village has met with both rising and falling prosperity over the last century, today it has been resurrected anew as a popular stopping-off point on the long road north. And so we did. Only to find a 4x4 convention there before us.

No contest.

From Beaufort West, four hours northbound on the Cape to Cairo road, we point our modern day ox-wagon east, our destination the historic frontier town of Graaff-Reinet, two hundred kilometres away. Endless vistas of acacia thorn and prickly pear and flat-top mesas ringed in rain, wrap themselves around our windscreen, many metres above the ground. It seems unusually green. For the desert.

The Karoo has not always been dry. Two hundred million years ago, when the southern hemisphere was a super-continent called Gondwana, the Karoo was a low-lying marsh in which dinosaurs and early mammals thrived. Then, the lakes dried up and became deserts and volcanic lava sealed this vast and stony record of time and tide. Today, in the museums and private collections throughout this region, fish scales, millennia old, glint from their ancient rocky graves and the skulls and bones of prehistoric monsters are forever stuck in the sands of drifting time.

The Karoo has not always been dry. Two hundred million years ago, when the southern hemisphere was a super-continent called Gondwana, the Karoo was a low-lying marsh in which dinosaurs and early mammals thrived. Then, the lakes dried up and became deserts and volcanic lava sealed this vast and stony record of time and tide. Today, in the museums and private collections throughout this region, fish scales, millennia old, glint from their ancient rocky graves and the skulls and bones of prehistoric monsters are forever stuck in the sands of drifting time.

The Valley of Desolation, a National Monument just outside Graaff-Reinet, reveals time's relentless passage. The layers of soft sediment have disappeared, leaving precariously leaning pillars of volcanic rock. Up to 120 metres high, these crumbling islands are a record of the ancient surface of the earth. The balancing columns of rock march down the rubble-strewn valley towards the plains. Way below, baboons pick their way over pieces of our mutual past.

Fifty kilometres north of Graaff-Reinet, tucked away among the foothills of the Sneeuberg is a more recent relic of the Karoo's extraordinary past, this time crafted by human hands. The dusty road bends into a blue bowl of hills and kopjes and suddenly in a hollow lined in yellowing poplar trees and willows, the geese have the right of way. In the nine years since Athol Fugard, the South African playwright, immortalised Miss Helen in his Road to Mecca, the sleepy village of Nieu Bethesda has been revitalised by a modern day pilgrimage to the Owl House.

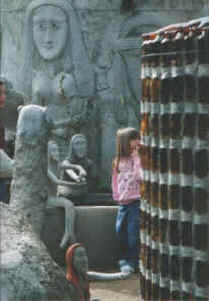

The tragic and enigmatic figure of Helen Martins still haunts her astonishing creation, born from a potent mix of religious fervour, sex and death, Omar Khayyam and William Blake. The Owl House is an eerie and evocative example of Outsider Art - driven individuals who are compelled to express their intense personal vision with whatever comes to hand. Miss Helen chose crushed glass and concrete.

Ashen women with beer bottle skirts lean forward in welcome, their fingers pointing east. Pallid mermaids beckon from sun-dried pools, directing attention towards the pilgrimage behind them. Wise men and camels and buddhas and sphinxes, owls and peacocks and lotus-legged potentates face towards EAST in frozen adoration. The word is picked out on the wire fence somewhere near the rising sun.

Thus far and no further beyond the old frontier. There are roads now, of sorts, into the lonely interior but they necessitate travelling light. So, we turn our taillights on the Great Karoo and backtrack south, heading for the hills. Rivers of grass, swollen with summer seed, sweep by my window, yellow daisies speckle the verges and water glints in seasonal water sources called Dry River 1, 2 and 3. Thunder rolls in from the Plains of Camdeboo.

The Great Karoo, to the north is divided from the Little Karoo in the south by a two hundred kilometre barrier, relic of ancient African Himalayas. Almost 150 years ago, Meiringspoort was forged through the massive Swartberg by the legendary road-builder, Andrew Geddes Bain. His son, Thomas, inherited his father's slide rule. Like the windmill, these long-dead visionaries opened the Karoo to the future, and their roads, today, provide portals to the past.

The Meiringspoort Pass criss-crosses the river-bed more than twenty times on its thirteen kilometre slalom through the ravine. Sailing above the narrow road and river, the coloured waves of sandstone rise and fall above our heads. Some plant and insect species here are unique only to this area, having had to adapt to such an extent to the tumultuous environment recorded in the zig-zagging strata of the hills.

Bains's son, Thomas, continued the family tradition with the second passage through these mountains and outdid even his father in the undertaking. The Swartberg Pass remains a feat of daring and engineering well worthy of its declaration as a National Monument in its centenary year of 1988.

The twenty-four kilometer pass begins innocuously enough, just outside Prince Albert, but soon the wagon-width road begins to climb upwards in switchback curves and knife-edge corners, past ruined reminders of the long-dead men who carved a road into these forbidding giants. The aloes give way to budding winter proteas and stony buttresses close out the declining afternoon sun. The summit is reached at 1,583 metres (5,000 ft) above sea level - as high as Johannesburg on the highveld plateau. The wind is slicing off distant snow and my fingers are numb with the sunset cold, up here beneath the clouds. Hundred-year-old walls of stone, hold the mountains back.

Down we trundle into the evening-shadows bound for Oudsthoorn, the ostrich-farming centre of the Klein Karoo. The cliff faces drop dizzily downwards towards a faint pinprick of light; a car approaching from the distant bottom of the pass. It has been cloudy for days now and the air is heavy with the smell of rain.

Oudsthoorn is as close as you'll come to a theme park in this part of the world. There's the Flying Ostrich restaurant in town and the huge wire ostrich egg that acts as Information Bureau for the annual Afrikaans Arts Festival held every year in March/April. Then there's a crocodile ranch, advertised by two enormous fibre-glass reptiles, in chef's hat and apron, licking their chops. Cheetahland and the Cango Wildlife Ranch welcome visitors into the reception area via another gaping-jawed croc. And from the curio-sellers on the side of the road, you can pick up an ostrich-egg tea-kettle. Just to remind you.

But hidden in the belly of the Swartberg, twenty winding minutes outside town, lies Oudsthoorn's real attraction, the Cango Caves.

Ancient paintings at the entrance to the Caves prove the San to have been the first to find the 5,3 km labyrinth but it seems to have remained unexplored until the entrance was rediscovered in 1780 by a herdsman named Klaas while searching for stray cattle. He told the farm manager of the Van Zyl farm, and Barend Oppelt and farmer Van Zyl went exploring.

The two men entered the muggy dark of the first great chamber by dangling themselves from leather thongs. With only the aid of an oil lamp they were not able to see the extent of their find and they estimated that the cavern was five miles long, three miles wide and one mile high. They were more than a few miles out but such excitability however is surely warranted by the awesome spectacle electricity has brought out of the dripping dark.

Accessed today down a long flight of stairs rather than a leather strap, Van Zyl's Chamber is pure Baroque. Rococo waves of rust and marbled sand sweep across the vaulted ceiling of the cavern. The walls drip with flowstone draperies like the Pipe Organ or bristle with seaweed tendrils. Stalactites cascade from above like the frosted breath of hidden gods. Gauzy columns, such as the ten metre high Cleopatra's Needle, float upwards to meet their other half. This could take some time. Stalactites have growth rings like trees and the calcite roses and cave popcorn, arum lilies and seaweed gardens are sculpted at rates of 3-5 cubic millimetres a century. The petrified weeping willow formation in the second great chamber is estimated at 1,5 million years old.

But the real-time world beckons of silicon and cell-phones, alarm clocks and appointments and alarums. Our desert liner heads for home. A crow perches on a wooden pole and draws the eye from veld and hill and sky. Relics of ancient mountain ranges raise their weathered brows to the skidding sun. The stonewashed sky is stitched in cloud and the horizon is streaked with rain. Locals say that this season has been the wettest in living memory. The endless tide, perhaps, has turned once more.